Pig semen-the Vector of virus Transmission (2)

The translator's words:

"Boar is good, good slope", by the same token, boar is bad, that is also bad slope. For almost 100% of the domestic large-scale pig farms that use artificial insemination, the impact of the health status of boars and semen on the whole production system is self-evident. this paper fully discusses the possibility and countermeasures of semen as a carrier of virus transmission from the aspects of the time when different viral pathogens are detected in semen, the effect on reproductive performance, routine prevention and health monitoring, biosafety system (facilities, logistics, etc.). In terms of depth, breadth and practicality, this article is a rare article on this topic. Greatness begins with sharing, and pig producers, health managers and professional boar station operators are highly recommended to watch, spread and even collect. In addition, whisper reminders: establishing multiple independent boar stations-not putting all your eggs in one basket is also a common strategy for semen risk management.

Pig semen-the Vector of virus Transmission (2)

Porcine semen as a vector for transmission of viral pathogens-Part 2

Dominiek Maesa,*, Ann Van Sooma, Ruth Appeltanta, Ioannis Arsenakisa, Hans Nauwynckb

A University of Ghent, Mellerbeck, Belgium, College of Veterinary Medicine, Animal Health and Obstetrics, Reproduction

A Department of Reproduction, Obstetrics and Herd Health, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent University, Merelbeke, Belgium

B Belgium, Mellerbeck, University of Ghent, College of Veterinary Medicine, Virology Laboratory, Immunology and Parasitology, virus discipline

B Department of Virology, Immunology and Parasitology, Laboratory of Virology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ghent University, Merelbeke, Belgium

Keyword Keywords:

Pig semen, pig, artificial insemination, virus, review / examination

Semen, Pig, Artificial insemination, Virus, Review

Follow up the above.

2.1 viruses present in pig semen and included in the OIE list

Viruses in porcine semen which are in the OIE list

2.1.2. Pseudorabies virus Aujeszky's disease virus (pseudorabies virus)

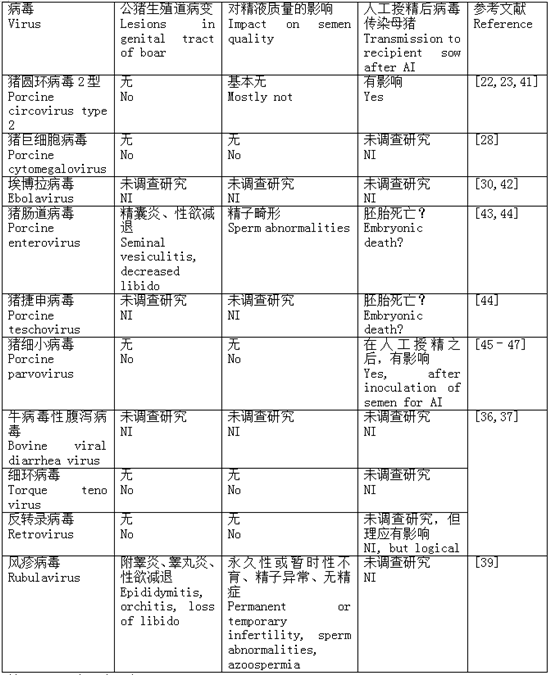

Table 4: viral pathogens present in pig semen but not included in the OIE list (2015): pathological changes of the reproductive tract of boars, the effects on semen quality, and the effects of virus transmission on sows after artificial insemination (AI).

Table 4: Viral pathogens not on the OIE list (2015) that have been found in porcine semen: lesions in the genital tract of boars, impact on semen quality, and transmission to recipient sow on artificial insemination (AI).

Abbreviation: NI, not investigated.

Abbreviation: NI, not investigated.

2.1 viruses present in pig semen and included in the OIE list

Viruses in porcine semen which are in the OIE list

2.1.3. Classical swine fever virus

Classical swine fever virus

Classical swine fever virus (CSFV) is a kind of enveloped RNA virus, which belongs to Flaviridae and Flavaceae. The virus has been eradicated from many countries or regions, such as Western Europe, North America and Australia [53]. However, after contact with wild boars, the virus may be introduced into domestic pigs. Between 1997 and 1998, during the epidemic of classical swine fever (CSF) in the Netherlands, two artificial insemination centres (AI) were infected, followed by the announcement that 1680 pig herds were suspected of being infected with classical swine fever [54]. This highlights the ability of artificial insemination centers to spread underlying diseases. The experiment showed that after being infected with classical swine fever virus, the days of detoxification of boar semen was as long as 53 days [11]. The virus had no effect on sperm morphology and motility, and the sperm concentration was normal. Insemination with infected semen may cause seroconversion in sows, and the virus may pass through the placental barrier, resulting in the death of the embryo, which can isolate the virus from the fetus [10].

Classical swine fever virus is an enveloped RNA virus belonging to the family flaviviridae, genus Pestivirus. The virus has been eradicated from many countries or regions such as Western Europe, North America, and Australia [53]. However, the virus has been periodically reintroduced into domestic pigs via contact with wild boars. During the CSF epidemic in the Netherlands in 1997 to 1998, two AI centers became infected and 1680 pig herds were declared CSF suspect [54]. This highlights the importance of potential disease spread by AI centers. Boars experimentally infected with CSF virus have been shown to shed the virus in semen for up to 53 days after infection [11]. The virus does not affect the semen morphology and motility, and the concentration is within the normal range. Sows that are inseminated with contaminated semen may show seroconversion, the virus may cross the placental barrier causing embryonic mortality, and the virus can be isolated from fetuses [10].

Because the virus is highly contagious, especially in its endemic areas, the impact will continue. Compared with piglets, infected breeder pigs may not show significant clinical symptoms and pathological features. If swine fever virus immune tolerant piglets are born and their clinical symptoms are normal, they can be dispersed for several months without any signs of disease or serological reaction [10].

The virus will remain important, especially in areas in which it is endemic, because the virus is highly contagious, and in contrast to piglets, infection in breeding pigs is not always associated with prominent clinical and pathologic signs. If clinically normal CSF virus immunotolerant piglets are born, they can spread the virus for months without showing signs of disease or eliciting a serologic response [10].

2.1.4. Foot-and-mouth disease virus

Foot-and-mouth disease virus

Foot-and-mouth disease virus is a kind of unenveloped small RNA virus, which belongs to the family small RNA virus and foot-and-mouth disease virus. The virus is endemic in Asia and some parts of Africa and South America [55]. Naturally infected boars can detect foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) virus in semen after 9 days, but the semen infected by artificial insemination will not infect breeding sows. It is not possible to explain the effect of virus on semen quality. Foot-and-mouth disease virus infection causes viremia, which then spreads to almost all tissues of the body, including the reproductive tract and the skin around the prepuce mouth [56]. The concentration of this virus in semen is low [12]. Foot-and-mouth disease has been eradicated in many countries, and boars are closely monitored in other countries, so the risk of the virus spreading through semen is low.

Foot-and-mouth disease virus is a small nonenveloped RNA virus that belongs to the family of picornaviridae, genus Aphthovirus. The virus is endemic in Asia and some areas in Africa and South America [55]. After natural infection, FMD virus has been recovered from semen from infected boars for up to 9 days, but AI with contaminated semen failed to transmit the disease to serviced sows [12]. An effect on semen quality has not been described. Infection with FMD virus leads to viremia, with subsequent dissemination of the virus throughout virtually all tissues of the body, including the genital tract and the skin around the preputial orifice [56]. The viral concentration in semen has been found to be low [12]. Because infections are officially eradicated in many countries, and because boars are intensively monitored in other countries, the risk for transmission of this virus by the semen is low.

2.1.5. Japanese encephalitis virus

Japanese encephalitis virus

Japanese Encephalitis virus (JEV) is a kind of enveloped RNA virus, which belongs to Flaviridae and Flaviridae. It is a mosquito-borne pathogen between humans and animals. The virus belongs to pig breeding pathogen and has a great impact on pig economy, especially in Asia and northern Australia, which may cause Japanese pig infertility [13]. Susceptible boars showed edema and testicular hyperemia after infection, and a large number of abnormal sperm appeared in semen, which significantly reduced the number of sperm and live sperm [13]. These symptoms are usually short-lived and most boars can make a full recovery. The virus has been isolated from testis of boars infected with orchitis and can be dispersed in semen for 5 weeks. If toxic semen is used to inseminate backup sows, the virus is easy to spread [13557].

Japanese encephalitis virus is an enveloped RNA virus that belongs to the family flaviviridae, genus Flavivirus. It is a mosquito-borne human and animal pathogen. The virus represents an economically important reproductive pathogen of breeding pigs, especially in Asia and Northern Australia, and may cause infertility in Japanese pigs [13]. Infection of susceptible boars resulted in edematous, congested testicles and semen with numerous abnormal spermatozoa, and significantly decreased total and motile sperm counts [13]. These changes are usually temporary, and most boars recover completely. The virus has been isolated from the testicles of boars with orchitis and also can be shed in the semen for 5 weeks. The virus can be easily transmitted if gilts are inseminated with infected semen [13,57].

2.1 viruses present in pig semen and included in the OIE list

Viruses in porcine semen which are in the OIE list

2.1.6. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (blue ear virus)

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus

Blue ear virus (PRRSV) is a kind of enveloped RNA virus, which belongs to arteritis virus family and arteritis virus genus. Infection with PRRS virus can cause reproductive disorders in pregnant sows, death in suckling pigs and respiratory diseases in pigs of different ages [58]. Adult boars usually have no or only mild symptoms. The virus spreads easily from animal to animal. Animals infected with PRRSV can be dispersed by saliva, nasal secretions, urine, feces and semen. It has been confirmed that PRRSV can be replicated through blood vessels into reproductive tract tissue. It has also been proposed that monocytes and macrophages infected in the blood and lymph of the reproductive tract be migrated to semen [155.59].

The PRRSV is an enveloped RNA virus that belongs to the family arteriviridae, genus Arterivirus. Infections with PRRS virus are associated with reproductive failure in pregnant sows, mortality in suckling pigs, and respiratory disease in pigs of all ages [58]. Usually, no or only mild symptoms are seen in mature boars. The virus is easily transmitted between animals. Infected animals can shed PRRSV in saliva, nasal secretions, urine, feces, and also in semen [19,20]. Vascular dissemination and replication of PRRSV in tissues of the reproductive tract has been shown. Also migration of infected monocytes and macrophages from the blood and lymph of the reproductive tract into the semen has been suggested [15,59].

The semen detoxification period of experimentally infected boars varied from 2 days [14] to 92 days [17] (average 35 days; Table 1). In a subsequent study, boars were euthanized 101 days after infection and PRRSV was isolated from the urethral bulbar gland. The difference of virus dispersal after infection may be caused by different factors, such as individual differences of boars [17Magin60], breeds [60], strain types and virus detection techniques (i.e. virus isolation, polymerase chain reaction [PCR], nested real-time PCR, reverse transcriptase PCR, pig bioassay). Using bioassay, infectious viruses were found in semen samples 4 to 42 days after infection [19]. Semen can disperse toxin even if there is no viremia and antibody neutralization.

The duration of shedding in semen samples of experimentally infected boars varies widely, ranging from 2 [14] to 92 [17] days after infection (mean 35 days; Table 1). In the latter study, PRRSV was isolated from the bulbourethral gland of a boar euthanized 101 days after infection. This marked variability in shedding may be due to different factors including individual boar variation [17J 60], breed of the boar [60], the type of virus strain, and the technique used for detection of the virus (i.e., virus isolation, polymerase chain reaction [PCR], nested real-time PCR, reverse transcriptase PCR, swine bioassay). Using a bioassay, infectious virus has been shown in semen samples from 4 to 42 days after infection [19]. The virus can be shed in semen, even in the absence of viremia and in the presence of neutralizing antibodies [17,60].

In the acute phase of the disease, boars are also less likely to have clinical symptoms of anorexia, drowsiness and respiratory tract. Different studies have shown that the effect of PRRSV infection on semen quality is very different. Some studies have shown that sharp changes in semen quality were detected 2 to 10 weeks after infection, such as decreased sperm motility, acrosome abnormalities, morphological and ejaculatory volume changes, while other studies found no abnormalities [19pc61].

During acute illness, in addition to anorexia, lethargy, and respiratory clinical signs, boars may also lack libido. The effect of PRRSV infection on semen quality varies considerably between studies. In some studies, drastic changes in semen quality, e.g., reduced motility, abnormal acrosomes, morphologic alterations, and volume of the semen, were observed 2 to 10 weeks after infection, whereas no abnormalities were found in other studies [19,61].

It has been confirmed that boars in the stage of acute infection can transmit PRRSV to breeding pigs through semen [61]. However, the ability of virus transmission depends on the number of viruses in semen, so the virus may not spread [62]. Prieto et al. [20] showed that the titer of PRRSV in single ejaculatory semen of infected boars was 7 × 10 ~ 2 TCID50/mL. If a single ejaculatory semen is diluted (15-30 times), the titer of the virus is about 4 × 10 ~ 10 TCID50/mL, which is equivalent to 3 × 10 ~ 3 TCID50 of PRRSV per 80 mL diluted semen. Sows mated with infected boars [61] or injected experimentally infected semen [19d21], even if there was no viremia, PRRSV seroconversion would occur. Prieto et al. [21] have shown that using semen containing PRRSV to inseminate serum-negative or unimmunized reserve sows, the conception rate is almost not affected, but early embryo infection and death may occur.

Transmission of PRRSV from fresh semen of acutely infected boars into breeding herds has been shown [61]. However, transmission does not always occur as it may depend on the amount of virus present in the semen [62]. In a study of Prieto et al. [20], the PRRSV titer in an ejaculate of an infected boar was 7 × 102 TCID50/mL. If the ejaculate is extended (15 the virus titer will be approximately 30 times), the virus titer will be approximately 4 × 101 TCID50/mL of extended semen, corresponding with a total amount of approximately 3 × 103 TCID50 of PRRSV in each dose of 80-mL extended semen. Sows bred by infected boars [61] or with experimentally contaminated semen [19,21] showed seroconversion to PRRSV, even in the absence of detectable viremia [17,60]. Prieto et al. [21] reported that insemination of seronegative or preimmunized gilts with semen containing PRRSV often has little or no effect on conception rates but may result in early embryonic infection and death.

2.1.7. Swine vesicular disease virus

Swine vesicular disease virus

Porcine vesicular disease (SVD) virus is an unenveloped small RNA virus, which belongs to the family RNA viroviridae and enterovirus genus. Outbreaks of SVD have been recorded in some countries in Europe, Asia and Central America. SVD virus and foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) virus may cause similar pathological changes. Therefore, attention should be paid to the differential diagnosis of SVD and FMD. SVD virus can be isolated from the semen of infected boars within 4 days after natural infection, but the semen infected by artificial insemination will not infect breeding sows.

The swine vesicular disease (SVD) virus is a small nonenveloped RNA virus of the family picornaviridae, genus Enterovirus. Outbreaks with SVD virus have been documented in some countries in Europe, Asia and Central America. Infection with the SVD virus may cause lesions similar to those on infection with the FMD virus. Therefore, SVD is important in the differential diagnosis of FMD. After natural infection, SVD virus has been isolated from infected boar semen for up to 4 days but AI with contaminated semen failed to transmit the disease to sows [12].

2.2 viruses present in pig semen but not included in the OIE list

Viruses in porcine semen which are not in the OIE list

2.2.1 Porcine circovirus type 2

Porcine circovirus type 2

Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) is an unenveloped small DNA virus, which belongs to the family circoviridae and circovirus genus. Pigs are also infected with PCV2 and other related diseases, generally referred to as PCV2-related diseases [63]. After being infected with PCV2 virus, sows will develop reproductive disorders, such as late miscarriage and stillbirth, but it is not common in actual production. Adult boars infected with PCV2 usually do not have clinical symptoms and lesions. The virus has been detected in natural and experimentally infected boar semen [24]. In the experimental infection, PCV2 DNA was detected in serum and semen on the 2nd and 5th day after infection, respectively. PCV2 viremia is tested before semen-associated viruses are detected, but semen may be dispersed even if there is no viremia. After experimentally infecting boars, some studies found intermittent detoxification of boar semen [24pr 25], while others found continuous detoxification of semen [26]. McIntosh et al. [27] showed that naturally infected boars occasionally dispersed their semen over a period of up to 27 weeks. These data suggest that semen may be an important carrier of PCV2. Viruses often contaminate seminal plasma, but PCV2 can be detected in both seminal plasma and sperm. There are few changes in morphology, motility and concentration of sperm [26]. Sows infected with PCV2 also showed few clinical symptoms [64].

Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) is a small nonenveloped DNA virus that belongs to the family circoviridae, genus Circovirus. Infections with PCV2 in pigs are associated with different disease conditions commonly referred to as PCV2-associated disease [63]. Reproductive problems in sows such as late-term abortions and stillbirths have also been described but are considered to be rare under field conditions. Mature boars infected with PCV2 generally lack clinical signs and lesions [24,26]. The virus has been detected in semen of naturally and experimentally infected boars [24]. On experimental infection, PCV2 DNA has been detected in serum and semen at 2 and 5 days after infection, respectively [24,26]. Detection of PCV2 viremia commonly precedes the detection of semen-associated virus, but semen shedding may occur in the absence of viremia. After experimental infection of boars, some studies found intermittent shedding in semen [24,25], whereas other studies observed continuous shedding of the virus [26]. McIntosh et al. [27] showed that naturally infected boars shed the virus sporadically in semen for up to 27 weeks. These data suggest that semen may be a significant vehicle for PCV2. The seminal plasma is usually contaminated, but PCV2 is not only detected in the non-sperm cell fraction but also in the sperm one [23,33]. Changes in semen morphology, motility, and concentration are not commonly found [26]. Clinical signs on PCV2 infection in breeding sows are rare [64].

When PCV2 is added to the semen, the experimental infection of unimmunized sows will occur reproductive disorders and fetal infection [41]. However, it is not clear whether the amount of PCV2 virus in semen is sufficient to infect sows or their fetuses in the case of natural infection. The virus can replicate in embryos without zona pellucida, resulting in embryo death. Delayed delivery or false pregnancy is not common in PCV2-related diseases. The number of piglet deaths may increase in litters affected by PCV2 [67].

Naïve sows inseminated with semen experimentally spiked with PCV2 exhibited reproductive failure, and their fetuses became infected [41]. However, it is not known if the quantity of PCV2 naturally shed in semen is sufficient to infect sows or their fetuses. The virus is able to replicate in zona pellucida–free embryos, leading to embryonic death [65,66]. Delayed farrowing or pseudopregnancy is less frequently observed with PCV2-associated reproductive failure. An increased number of nonviable piglets may be present in PCV2-affected litters [67].

2.2.2. porcine cytomegalovirus

Porcine cytomegalovirus

Porcine cytomegalovirus or porcine herpesvirus type 2 is a DNA virus belonging to the herpesviridae, herpesviridae, but not to any genus. Adult pigs are infected with porcine cytomegalovirus, usually subclinically. After boar infection, virus can be detected in testis and epididymis [28]. It is not clear whether the ejaculated semen is toxic.

Porcine cytomegalovirus or suid herpesvirus type 2 is a DNA virus that belongs to the subfamily betaherpesvirinae of the family herpesviridae but is not assigned to any genus. Infection with porcine cytomegalovirus is usually subclinical in adults. After infection in boars, the virus was detected in the testis and epididymis [28]. Shedding of virus in ejaculated semen has not been determined.

2.2.3. porcine parvovirus

Porcine parvovirus

Porcine parvovirus (PPV) is a non-enveloped small DNA virus belonging to the family Parvoviridae, genus Parvovirus. The virus is common in pigs. The main transmission routes of PPV are oronasal transmission and placental transmission. The virus has been isolated several times from naturally infected boar semen. Boar semen can shed virus during acute infection [34]; although continued shedding in later stages has not been confirmed, PPV immune-tolerant individuals may develop due to early uterine infection [68]. It may also be fecal particles containing the virus, or male reproductive organs, that cause semen contamination [45, 46]. In boar herds, infection is usually asymptomatic. Experimentally infected boars showed little change in fertility or libido [46], sperm count, semen volume, sperm motility or morphology [47]. After PPV infection, fertile sows usually show only reproductive impairments: return to estrus, reduced litter size, increased number of mummified fetuses [69]. The role of PPV-contaminated semen in causing reproductive failure is unclear.

Porcine parvovirus (PPV) is a small nonenveloped DNA virus that belongs to the family parvoviridae, genus Parvovirus. The virus is ubiquitous in the pig population. The main transmission routes of PPV are oronasal and transplacental. The virus has been isolated many times from semen of naturally infected boars. Boars can shed the virus in semen during the acute phase of infection [34]; shedding beyond this phase has not been demonstrated, but the possibility of immunotolerant carriers of PPV as a result of early in utero infection has been suggested [68]. Semen may also become contaminated by fecal particles containing virus, or within the male reproductive tract organs [45,46]. In boars, usually no clinical signs after infection are observed. On experimental infection in boars, no alternations in fertility or libido [46] or in sperm output, ejaculate volume, motility, or morphologic defects [47] were found. In breeding females, the major and often only clinical sign of PPV infection is reproductive failure: return to estrus, fewer pigs per litter, and increased numbers of mummified fetuses [69]. The role of semen contaminated with PPV in creating clinical reproductive problems has not been clearly established.

Recently, PPV4, a novel parvovirus belonging to the genus Bocavirus of the Parvoviridae family, was detected in 5 (38.5%) of 13 semen samples [70] and in half of semen samples in the study by Csagola et al.[71]. The impact of the virus on the health of swine populations is uncertain. Other novel porcine parvoviruses (PPV2, PPV3, porcine parvovirus 1 and 2, other markers 6V, 7V porcine bocavirus, porcine boca-like virus) were found in different pig herds in Hungary, but could not be detected in semen [71].

Recently, a novel parvovirus namely PPV4, belonging to the family parvoviridae, genus Bocavirus, was detected in 5 out of 13 (38.5%) semen samples [70], and in one out of two semen samples in a study by Cságola et al. [71]. The role of this virus in swine health has not been determined. Other novel porcine parvoviruses (PPV2, PPV3, porcine bocaviruses 1 and 2, other porcine bocaviruses labeled 6V and 7V, porcine boca-like virus) were found in pigs from different herds in Hungary, but they could not be detected in semen [71].

To be continued...

To be continued…

Related

- On the eggshell is a badge full of pride. British Poultry Egg Market and Consumer observation

- British study: 72% of Britons are willing to buy native eggs raised by insects

- Guidelines for friendly egg production revised the increase of space in chicken sheds can not be forced to change feathers and lay eggs.

- Risk of delay in customs clearance Australia suspends lobster exports to China

- Pig semen-the Vector of virus Transmission (4)

- Pig semen-the Vector of virus Transmission (3)

- Five common causes of difficult control of classical swine fever in clinic and their countermeasures

- Foot-and-mouth disease is the most effective way to prevent it!

- PED is the number one killer of piglets and has to be guarded against in autumn and winter.

- What is "yellow fat pig"? Have you ever heard the pig collector talk about "yellow fat pig"?